In many situations, data collection is performed iteratively in order to solve a problem, i.e. it is collected at repeated intervals over time to update your state of knowledge; for example, in search-and-rescue, and surveillance activities. On each data-collection iteration, there is the question of what kind of data you should collect. This can be as simple as where in a space you should move to make your next data collection step (changing what areas of the space you can see or detect), and/or it can be a question of what type of sensor you deploy.

Even in situations where a static sensor network is needed for monitoring purposes - for example, an alarm network to detect toxic gas leaks - there is the question of where you should place the sensors in order for the network to operate optimally and be robust to inevitable sensor failure over time.

Through contract work with the UK Ministry of Defence's DSTL (Defence Science and Technology Laboratory), we have developed a new statistical framework - MIDAS - to answer these exact questions. MIDAS (Maximal Information for Data Acquisition Strategy) was developed over 2 years with DSTL. It was originally designed to systematically decide the best strategy for collecting sensor data, in order to detect and locate a nefarious transmitter in an urban cityscape.

On the left, is an example of MIDAS deciding on the number and placement of sensors on a set of buildings for optimal surveillance coverage. The scene is viewed from above in 2D, buildings are depicted with white blocks, and sensors with coloured dots (with each sensor's field of view displayed with coloured shading). We see MIDAS experiment with the number of sensors and their placement before it concludes that 4 sensors provide sufficient information (over 99% coverage) and outputs a library containing a selection of optimal placement options.

In our latest development phase we extended MIDAS to be able to independently play a simulated game against a human. Despite the simplicity of the game, we were excited to see that MIDAS consistently beat human opponents; i.e. MIDAS found the location of the human’s virtual flag in less steps than in took for the human player to find MIDAS's flag.

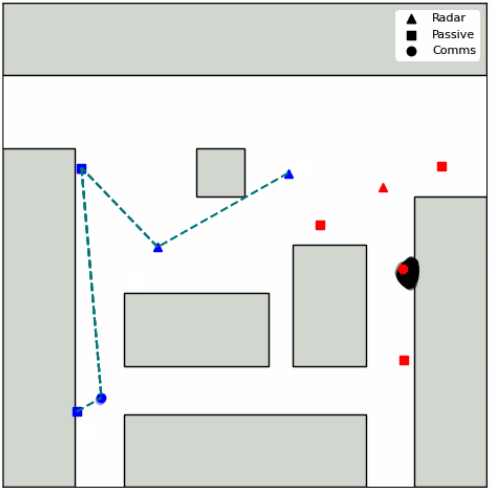

The right image shows a snapshot from this particular game, with the human team players in red, and MIDAS’s in blue. Both teams are attempting to capture the opponent’s communications station (circles), by moving 4 multi-functional drones through the space (triangles or squares depending on detection mode activated in the current step).

As the complexity of problems increases, e.g. with numerous multi-functional drones moving in 3 dimensions, it becomes impossible for the human decision maker to make robust and optimal strategy decisions. A human cannot make well-informed and effective decisions in high dimensions. MIDAS can.

On each time-step in this simulated game all drones collect fresh data and relay it back to their communications station (requiring direct or indirect line of sight - green dashed line). Each player then makes a decision on what to do next based on their latest dataset. To the left we show an animation of a typical set of MIDAS moves for this particular game. There are several interesting choices it made that gave it the edge over the human players - such as moving up close to buildings to maximise sensor field of view, and using only a single drone to monitor the bottom horizontal corridor.

Every new application of MIDAS has delivered new, and often counter-intuitive (until you understand the reason for its decision), approaches to data-collection decision making. MIDAS is genuinely our most exciting tool to date.

MIDAS has also been extended to optimise with the knowledge that a number of sensors might fail at any given time, to guarantee robustness to failure.

MIDAS has since been adapted for use in optimising communication transmitter/receiver configurations for communications-network design. We have validated this approach for designing communications networks for use with connected and driverless vehicles with funding from Zenzic, where its ability to ensure consistent coverage even when a transmitter/receiver drops out is essential. More information on this project, please visit our Zenzic project pages.